A little over a week after the 2020 election, when President Trump continued to tweet that the election had been rigged against him and that Dominion voting machines had deleted votes for him, 59 election security experts issued a public letter. It reads:

“Anyone asserting that a US election was “rigged” is making an extraordinary claim, one that must be supported by persuasive and verifiable evidence. Merely citing the existence of technical flaws does not establish that an attack occurred, much less that it altered an election outcome. It is simply speculation…

“To our collective knowledge, no credible evidence has been put forth that supports a conclusion that the 2020 election outcome in any state has been altered through technical compromise.”

One of the organizers of that letter was School of Information alumnus Joseph Lorenzo Hall (Ph.D. ’08), a noted election security expert and Senior Vice President for a Strong Internet with the Internet Society. “There’s definitely never been a need for a letter like this,” Hall said.

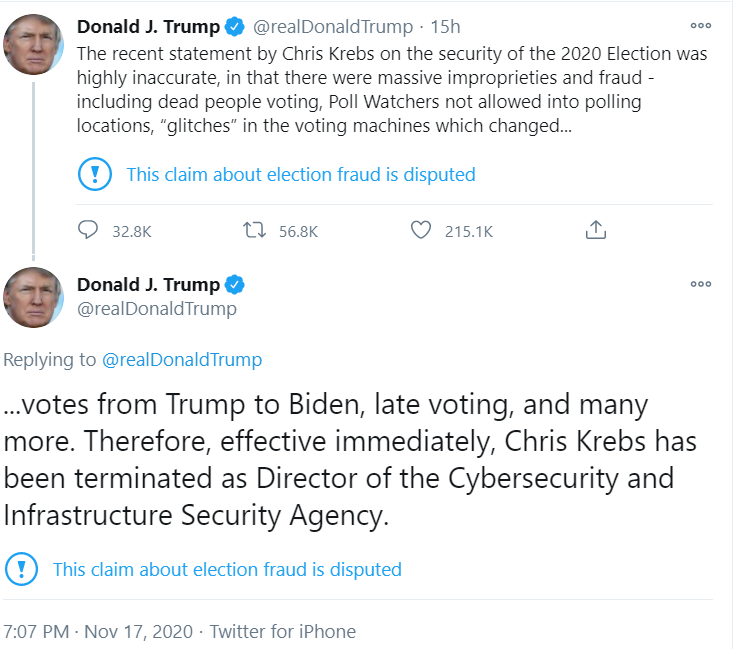

Signees of the letter included major players in the election security field including co-organizer Matt Blaze of Georgetown, Ronald Rivest of MIT, and J. Alex Halderman of the University of Michigan. They hoped its publication might buttress Chris Krebs, the embattled DHS Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Krebs was attempting to fight misinformation claims on the agency’s Rumor Control website and in the press and eventually reached out to the voting security expert community for support, which led to the publication of the letter on November 16, 2020.

“It became clear that the president and those that would support his inaccurate view of reality were using some of our own voting system security research to support their claims that none of these machines can be trusted,” Hall said. “That was, frankly, BS.”

The letter of support was published on November 16. On November 17, CISA Director Krebs was fired via a presidential tweet.

Lunchtime reading as a career

When Hall started at Berkeley as a Ph.D. student, it was in astrophysics. He soon knew something wasn’t right; he realized that what made everyone around him get up in the morning — wanting to solve the (physical) mysteries of the universe — just wasn’t what made him tick. “When I thought hard about what I wanted to do with my life, or what kind of legacy I wanted to leave, it was really about ‘helping people'. When I thought about it it seemed like there were very few ways to be in astrophysics and help people.”

So he spent time considering to what he could apply his particular set of skills and then happened to attend a talk by Berkeley Law and School of Information Professor Pamela Samuelson on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and how it was inhibiting cryptography research at the time. It turned out to be a life-changing lecture for him.

“These were the kinds of things I thought about and spent a lot of time reading about on my lunch break,” Hall said. “I couldn't believe it hadn't occurred to me before, that people like Pam and Ross Anderson (the pioneering security engineer at University of Cambridge) got paid to think about these things I thought about on my lunch break.”

Maybe he could get paid to think about them, too?

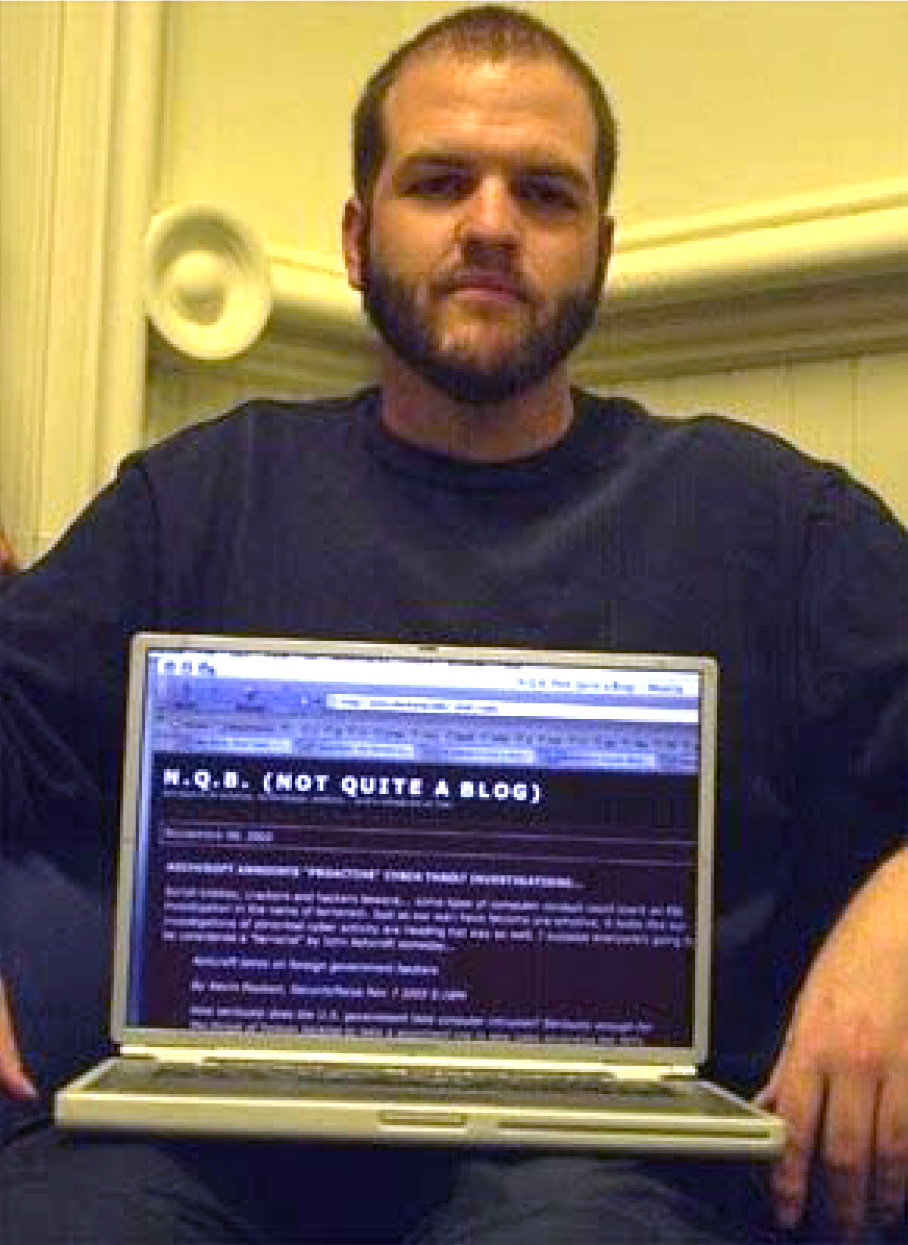

Hall left the astrophysics program and moved to the I School, where he began researching the security and opacity of voting systems. In 2003, a hacker broke into Diebold Election Systems, Inc. (now known as Premier Election Solutions) and retrieved five years of internal email list traffic. Hall and other student activists made the lists public on their personal websites for, as he says, “researchers and good government people to search through for wrongdoing.” He received a cease and desist letter from Diebold for posting the documents that showed possible security flaws in the company’s voting machines. This led to what Hall calls a “Whack-a-Mole Protest,” where one student researcher would post the lists on their website, Diebold would send a cease and desist letter, that student would remove them, and then another student would post them, thereby assuring the information was always available.

These days, Hall said, voting system vendors are more forthcoming, although still not completely transparent. They now accept vulnerability reports, and there’s now an open-source nonprofit, Voting Works that helps implement systems that Hall worked to establish.

Things have also gotten better in the regulatory sense, too, Hall said. The federal body that oversees security and technical aspects of voting systems, the US Election Assistance Commission, is more transparent and forthcoming than it has been in the past, and according to Hall, it appears things will only get better.

Public interest technology: Helping People

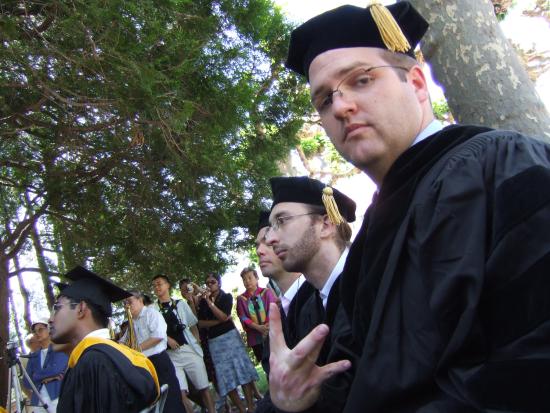

In 2008, the former astrophysics student received his doctorate from the I School. His dissertation was titled Policy Mechanisms for Increasing Transparency in Electronic Voting, and his thesis advisor was Pamela Samuelson.

Since then, Hall has built a career centered around public interest technology — helping people. He believes there are needs society has left unfulfilled by for-profit endeavors and government action. “If we can set aside some funds to ensure that good things happen free from those influences,” Hall said, “we can better ensure that society has more of its needs addressed.”

He recently moved on after seven years with the Center for Democracy and Technology — an organization whose first stated mission and principle is to “Champion policies, laws, and technical designs that empower people to use technology for good while protecting against invasive, discriminatory, and exploitative uses.”

His new position with the Internet Society began in September 2019. Half of all projects the organization runs fall under his purview and include the “Internet Strong” projects which focus on security, privacy, and ensuring the Internet remains open, secure, globally-connected and trustworthy. He’s acutely aware of the responsibility he shoulders, overseeing a large staff of “experts all working on a handful of projects focused on Internet routing security, end-to-end encryption, the Internet Way of Networking, and working on countering China and Russia’s ideas about more centralized versions of the Internet” that he says, “would be bad for all of us.”

Hall has built a career standing up for truth in technology, which is why those who know him weren’t surprised that he was one of the organizers of the letter attesting to the integrity of the 2020 election. Enabling people to understand or accomplish things that they couldn’t have done before is the core of his passion, he said, and technology is a great place for that. “I’m just as fulfilled helping get a printer back running, as publishing a big report or vanquishing a foe,” he said. “And I hope to build a tiny technologist within everyone I meet, because their lives and our lives will be better.”