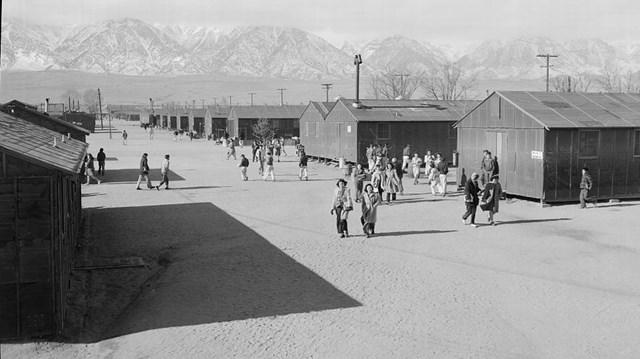

When the Bancroft Library received over 100,000 Japanese-American internment “individual record” forms (WRA-26) from the National Archives and Records Administration after World War II, they had no idea these forms would become the only complete set left in existence. In 2019, the National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites program provided a grant to digitize the forms to create a long term digital archive of the records, as well as to extract the data held in the forms.

The WRA-26 forms are a census-type two-page form that contains demographic, educational, occupational, and biographical data about every person incarcerated at internment camps during the war.

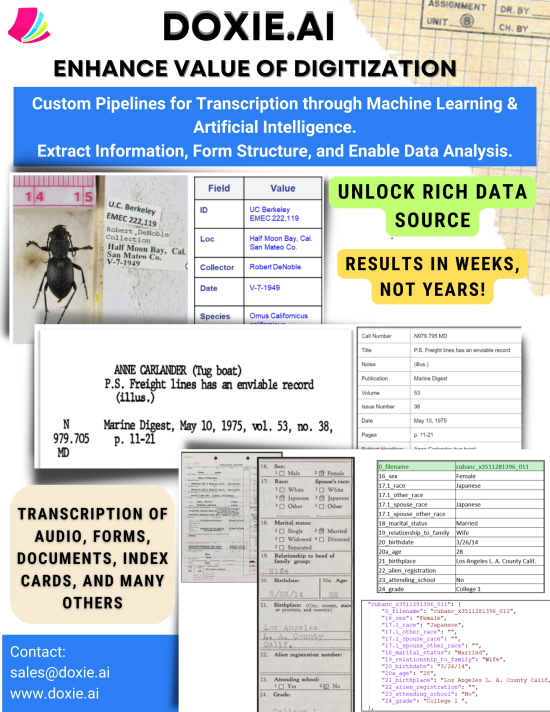

Mary Elings, Interim Deputy Director and Head of Technical Services at the Bancroft Library, the principal investigator behind this project, wanted to explore how the library could efficiently extract the fielded data in these forms. To help with transcribing and extracting large quantities of data, the Library turned to a few then-Master of Information and Data Science students who were completing their capstone project, a precursor to their current work. Since then, the team has formed Doxie.AI, a firm that builds custom pipelines to extract information from challenging data sources.

In this case, many forms contained entirely handwritten responses as well as notations, annotations, and other marginalia, which were difficult to capture in the traditional machine transcription process.The team at Doxie fine-tuned their models to try and account for the complexity and inconsistencies in these forms and worked on digitizing one camp at a time.

“Transcribing the forms was a moving experience for us,” said Vijay Singh (’20), founder and CEO of Doxie.AI. “We understood and knew that this would have a tremendous impact in terms of research, awareness, and getting that information back to those communities.”

The project also raised ethical concerns, considering the presence of sensitive personal information such as Social Security numbers in the forms and how the information was collected under duress from forcibly relocated individuals.

To address part of this issue, Bancroft worked with Doxie.AI to customize its model, automatically redacting Social Security and Alien Registration numbers from the dataset to avoid collecting and aggregating this data. They also worked to eliminate bias in datasets by standardizing Japanese names and places using custom dictionaries.

“Transcribing the forms was a moving experience for us. We understood and knew that this would have a tremendous impact in terms of research, awareness, and getting that information back to those communities.”

After this work was completed, The Bancroft Library, working with partner Densho, a community memory organization dedicated to preserving the history of incarceration, as well as the Library’s Office of Scholarly Communication Services, held a community advisory group meeting with former internees, their descendants, and others to discuss concerns about how this information was collected, where a consensus emerged that the value of providing access to the information outweighed the potential harms.

As of now, Doxie.AI has finished transcribing the records and the Bancroft Library is moving on to next steps — data cleanup and further exploration of ethical access. Elings hopes to eventually be able to connect these records with data sets being developed by Densho.

The School of Information was formerly the School of Library Science at UC Berkeley. This project is an important example of the ongoing connection between librarians, information, and data scientists. In this case, the Doxie.AI team demonstrated how machine learning can help libraries transcribe and structure data more efficiently.

“Traditionally, digitization has meant preservation or getting better access in digital form,” said Singh. “They have not traditionally looked at this as getting more structured extraction from the data. [Now library services companies] pitch our work as sort of a second stage; we take those digitized images and extract data depending on the area of interest.”

“There is great potential for machine learning and AI in libraries. There is a lot of discussion right now in library forums around what AI [and machine learning] can do to help us work better and faster,” added Elings.

“I want people to understand that we’re not just a keeper of old stuff; rather libraries are using technology to innovate on a regular basis, to figure out better, faster, and more computationally ready ways of making [these records] available to researchers.”