Pioneering Berkeley alumna Eliza Atkins Gleason (M.A. ’36) was the first African American to earn a doctorate in library science

By Cheryl Knott

of Louisville Photo Archives)

At the height of the Great Depression, in 1936, a young black woman named Eliza Valeria Atkins completed her M.A. in Library Science at the University of California, Berkeley. She had already demonstrated her commitment to learning and to the library profession by earning two bachelor’s degrees, one at Fisk University and the other, in library science, at the University of Illinois. Additionally, she had held positions as an assistant librarian and as head of the library at the Municipal College for Negroes in Louisville, Kentucky. As she readied herself to return to the profession with her master’s degree, she could not have foreseen that her work would be widely influential and that her career would be the subject of entries published in the World Encyclopedia of Library and Information Services, Notable Black American Women, the Historical Dictionary of Librarianship, and others, including, of course, Wikipedia.

In the late 1930s, she worked on her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, where in 1940 she became the first African American to earn a doctorate in library science. One of her mentors there, Carleton B. Joeckel, had worked from 1914 to 1927 as director of the Berkeley Public Library, overseeing a significant increase in book circulation and the creation of new branches. Joeckel also taught the public library administration course offered by UC Berkeley’s Department of Library Science. His dissertation, completed at Chicago in 1934, was published by the University of Chicago Press as The Government of the American Public Library in 1935, the year he joined the University of Chicago Graduate Library School faculty. Although Joeckel’s and Atkins’s time in Berkeley did not overlap, their familiarity with the city and the university gave them something in common beyond their research interests. Under his guidance, Eliza Atkins completed her dissertation, “The Government and Administration of Public Library Service to Negroes in the South,” in 1940.

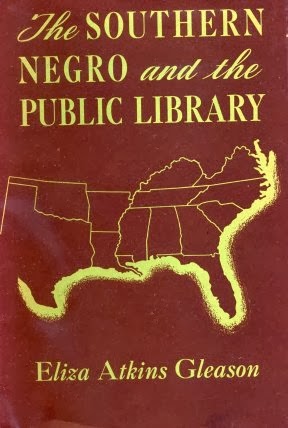

The next year, the University of Chicago Press published her dissertation as a book, titled The Southern Negro and the Public Library, under her married name, Eliza Atkins Gleason. Her research documented the existence of many racially segregated southern public libraries. Gleason noted pointedly that cities and towns in the South did not have the financial means to create two separate systems that were equal in terms of facilities, staff, and collections. She suggested that the better alternative was to fund a single library serving all equally. Joeckel endorsed the work with a blurb on the inside front flap of the book jacket: “Accurate and detailed in its factual basis, and carefully objective in its method of treatment, the study breaks new ground with extensive information concerning the dual system of service . . . .” The book was widely and positively reviewed and, two decades before passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, marked an early turning point in how some whites thought about public libraries and the people they served.

From Chicago, Gleason went to Atlanta University where she served as Dean of the newly established School of Library Service, designed to graduate African American students who would serve in the public libraries Gleason had studied as well as in academic libraries at southern black colleges and universities and elsewhere. After World War II ended, Gleason left Atlanta to join her husband, a physician, in Chicago. There she raised a daughter — who went on to become a college professor — and continued to work in the library field, eventually becoming the first African American to serve on the Council of the American Library Association. In recognition of Gleason’s profound effect on library science education and on libraries, the Library History Round Table of the American Library Association named its periodic award for the best book in library history after her.

Born in North Carolina, educated in Nashville, Urbana-Champaign, Berkeley, and Chicago, and employed in racially segregated institutions, Gleason navigated geographic, educational, and professional boundaries even as they shifted with the times. Her thinking and her doing neither started nor ended at the University of California, but Berkeley provided a West Coast experience that likely broadened her southern and midwestern perspectives even as she no doubt brought a unique perspective to the school. Gleason was one of the few librarians and library-science educators of her generation who understood the complexities of race hidden in the popular and professional rhetoric touting equal access to information and reading material. An influential figure in librarianship’s history, Gleason remains relevant as libraries and information schools identify and address continuing information injustices.

Cheryl Knott is a professor in the School of Information at the University of Arizona.

Selected Sources

- Cheryl Knott, “The Publication and Reception of The Southern Negro and the Public Library.” in Race, Ethnicity and Publishing in America. Editor Cécile Cottenet. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow, University of Massachusetts Press, 2015.

- University of Louisville Women’s Center, “Obituary – Dr. Eliza Atkins Gleason.”

![Library, University of California [at Berkeley] ca. 1895-1936. (Online Archive of California) library c.1900](/sites/default/files/styles/sidebar/public/article_image/library-adjusted.jpg?itok=7lvcJwun)