Morgan G. Ames, assistant adjunct professor at the School of Information, explores the rise and fall of the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project in her new book, The Charisma Machine: The Life, Death, and Legacy of One Laptop Per Child. Over the course of the book, Ames examines the utopian visions that fueled the project and its failures in understanding the role of technology in education.

The Formative Years of OLPC

In the mid-2000s in Silicon Valley, the OLPC project was still very much at the height of its popularity. Started in 2005 by MIT Media Lab co-founder Nicholas Negroponte, the OLPC project promised to transform children’s lives across the Global South with a portable, durable, and inexpensive laptop, referred to as the XO.

After talking with a friend who was interested in joining the organization, Ames grew fascinated with the project and began to dig into some of its central assumptions. Ames explains, “it gradually grew from there into a critical history, and then into an ethnographic investigation to see how OLPC’s hopes were faring with the kids who were their primary beneficiaries.”

Ames first started researching the OLPC project in 2007, early on in her doctoral program at Stanford, just after receiving her master’s in information management and systems from the UC Berkeley School of Information. She also received her B.A. in Computer Science at Berkeley, and is thrilled to be back on campus as faculty at the I School: “I feel like, in so many ways, this is my intellectual home.”

By the spring of 2008, Ames was conducting interviews with anyone who had worked on the project. Around the same time, however, co-founder Negroponte announced that he wanted to scrap the open source software that they had been planning to use on the computer and use Windows instead. “This was just a massive betrayal to all of the people involved in free and open source software who had committed to this project,” Ames said. “So people were quitting right and left — it was just a disaster.” As a result, many former employees simply didn’t want to be associated with the project anymore, and refused or did not answer her requests for interviews.

That’s when she realized that there were other places she could look for more information. “I actually found that their public discussions on mailing lists, online and other places, captured their thoughts about the project and the evolution of their thoughts about the project much better than my interviews tended to,” said Ames. After tracking these online posts, she began to piece together a story on what the laptop was meant to do in the world. She would later spend seven months in Paraguay across three years to actually see the XO laptop in use, talk to project leaders there, and spend time with those who had received the laptop.

How the XO Charmed Silicon Valley

While conducting research, Ames was fascinated by how alluring the XO laptop appeared to those in the tech industry. She observed how the laptop itself, and not the individuals who inspired it, came to embody the ambitious ideas behind the OLPC project. “I started thinking about how the laptop began to have its own kind of authority in these circles: even mentioning it came to stand in for a particular kind of joyful, technically deep experience they wanted more children to have with computers,” commented Ames.

Delving into sociological theory to better understand different forms of authority, she applied Max Weber’s concept of charismatic authority to the XO laptop. Ames connected this with an observation from science and technology studies that machines can have agency themselves, taking on meanings and acting in the world beyond the intentions of the designers. She also observed how the social sciences discuss authority as not a natural occurrence, but instead as something that is produced by a set of social choices and technical constraints that already exist.

“Charisma is ultimately conservative — it may promise to quickly and painlessly transform our lives for the better, but it is appealing because it just amplifies existing values and ideologies,” said Ames.

The OLPC project’s charismatic machine, according to Ames, “promoted a vision of the world where children across the Global South would have the opportunity to have the same kinds of formative experiences with a computer that these adults remembered having.” The memories of tinkling with early computers, learning the ins and outs of the machine and beginning to code, were intrinsically tied to the development of the XO laptop; Ames calls this homage to childhood experiences “nostalgic design.” In reality, this translated to underpowered laptops with a lack of features like fancy graphics and large memory storage units — features that were increasingly necessary for a media-rich online world.

Hundreds of discussions across the Internet in the mid-2000s compared the XO laptop to Commodores, Amigas and Apple IIs, the early computing systems that had been used decades before by OLPC developers and many others. The facilitation of “nostalgic design” proved to be a crucial mistake that ignored the needs and desires of the kids receiving the laptop. “They want a computer that could take advantage of the media-rich web, and the XO just couldn’t deliver there,” said Ames.

Between A Child in Paraguay and An Aging Machine

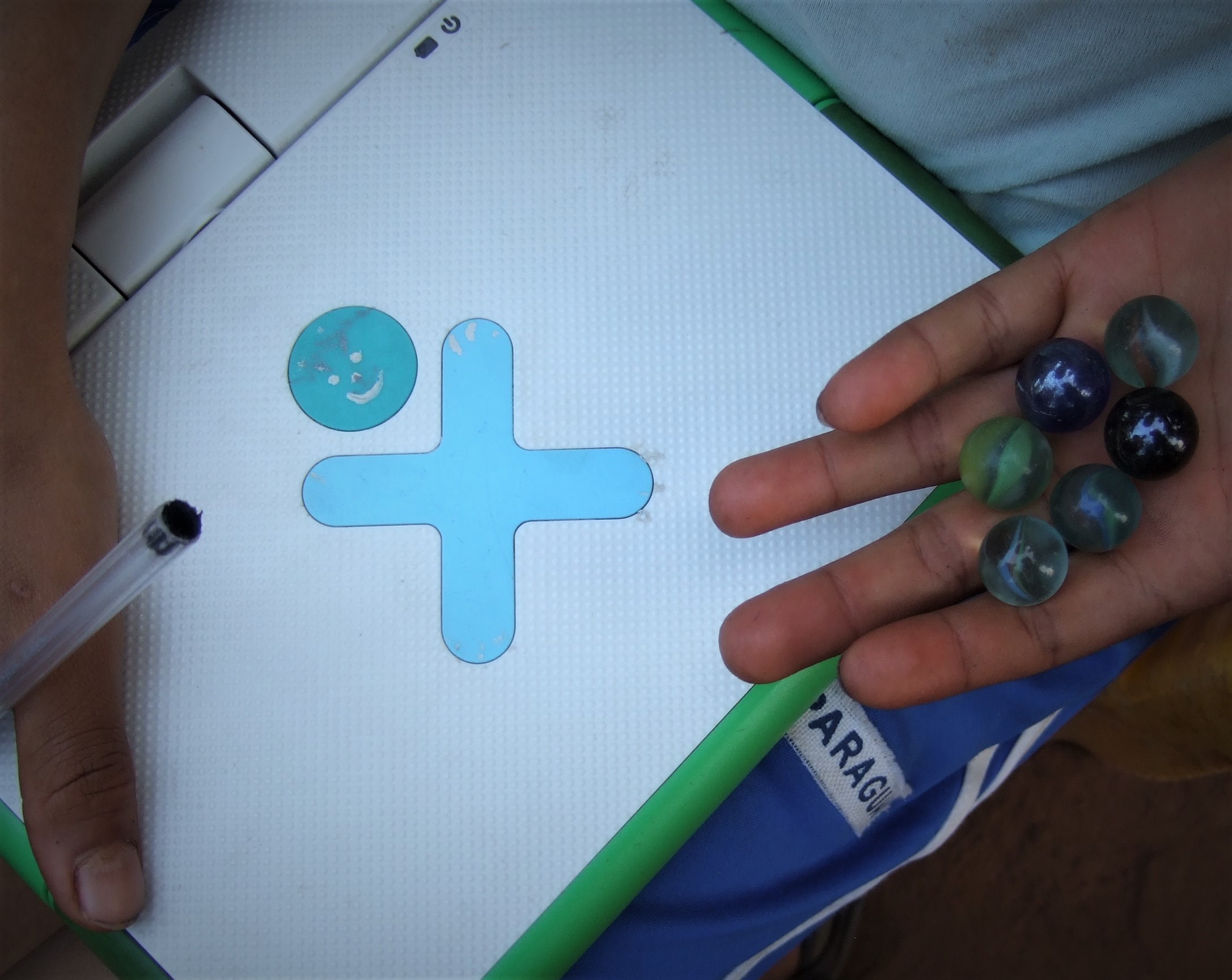

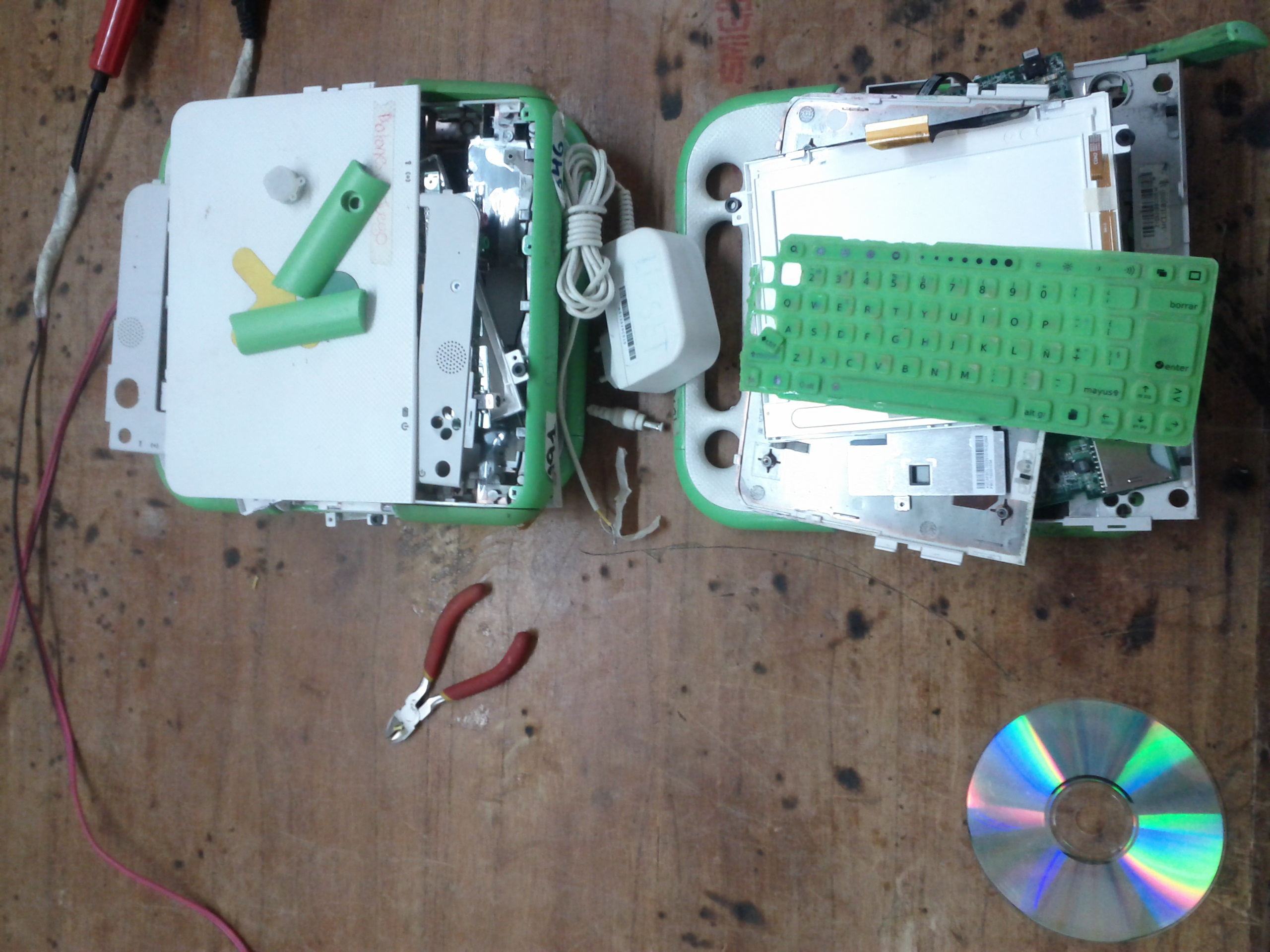

This disconnect between developers for the OLPC project and the kids from the Global South translated to an inability to meet the utopian goals that once fueled the project. In Paraguay, Ames saw in 2010 that over half of the kids who received an XO laptop just weren’t interested in using them. The machine was ten years behind the curve and frustrating to use, and most would rather go outside and spend time with their friends and families. About fifteen percent had broken machines. And most of the rest wanted to use their laptops to surf the Internet, watch movies, listen to music, and play simple games.

There were, however, a few children who showed potential in their use of the XO laptop. Ames highlights the distinction between consumptive behaviors and productive behaviors that researchers in the education world often focus on, in part because the OLPC project was specifically interested in the kids who exhibited more productive behaviors. When searching for kids who fit these criteria, she found a handful: some were photo-blogging, some learned some basic repair skills, and a few joined code clubs and were interested in Scratch.

“In 2010,” she shared, “of the 4,000 or so kids with laptops then, maybe about 40 were doing anything along these lines.” By 2013, few children were using their laptops at all.

Furthermore, Ames found that these children were successful not only because they were “naturally” interested, but primarily for external reasons, mainly family. This isn’t anything new, she emphasized — educational research shows that family and mentorship, as part of the social factors of the learning process, are central to a child’s educational success. Moreover, the effect of this interest was ultimately relatively small. “I think the program enriched their lives in various ways, but I don’t think it transformed them,” said Ames.

The Future of Tech-Driven Educational Reform

Examining the OLPC project in the context of the tech world more broadly, Ames sees some parallels. “A lot of tech-development projects after OLPC did become more humble,” Ames comments, noting the more realistic goals of some recent tech projects. But more often than not, she encounters the same mentality of the “smartest person in the room” that pervades the tech world and favors short-term “disruption” over effective educational reform.

Reflecting on the current state of tech-driven projects meant for educational reform, Ames noted, “people still tend to be wildly utopian, completely disconnected from schools, completely disconnected from the experiences of students and teachers on the ground.” To counter this, she recommends “not just involving local actors, but really centering them and their needs, experiences, and complications.” By thinking about the social factors of education and reflecting on the actual experiences of teachers and students, Ames thinks that future projects can find more success.

“People are what make education what it is,” said Ames. “Learning is social.”