-

The Berkeley School of Information is a global bellwether in a world awash in information and data, boldly leading the way with education and fundamental research that translates into new knowledge, practices, policies, and solutions.

-

The School of Information offers four degrees:

The Master of Information Management and Systems (MIMS) program educates information professionals to provide leadership for an information-driven world.

The Master of Information and Data Science (MIDS) is an online degree preparing data science professionals to solve real-world problems. The 5th Year MIDS program is a streamlined path to a MIDS degree for Cal undergraduates.

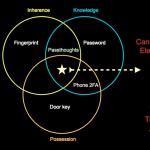

The Master of Information and Cybersecurity (MICS) is an online degree preparing cybersecurity leaders for complex cybersecurity challenges.

Our Ph.D. in Information Science is a research program for next-generation scholars of the information age.

-

The School of Information's courses bridge the disciplines of information and computer science, design, social sciences, management, law, and policy. We welcome interest in our graduate-level Information classes from current UC Berkeley graduate and undergraduate students and community members. More information about signing up for classes.

-

Research by faculty members and doctoral students keeps the I School on the vanguard of contemporary information needs and solutions.

The I School is also home to several active centers and labs, including the Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity (CLTC), the Center for Technology, Society & Policy, and the BioSENSE Lab.

-

-

I School graduate students and alumni have expertise in data science, user experience design & research, product management, engineering, information policy, cybersecurity, and more — learn more about hiring I School students and alumni.

-

-

September 27, 2024, 3:10 pm – 4:30 pmMay 18, 2024, 2:00 pmApril 24, 2024, 12:30 pm – 1:45 pmFebruary 21, 2024, 12:10 pm – 1:30 pm