Imagine this: you’re the CEO of a hydroelectric plant and its subsidiaries. The plant is riddled with security vulnerabilities, leaving it open to attack from rogue nations and others who look for opportunities to disrupt critical infrastructure in the US. How do you prevent a malicious cyberattack, all the while maintaining service for your customers?

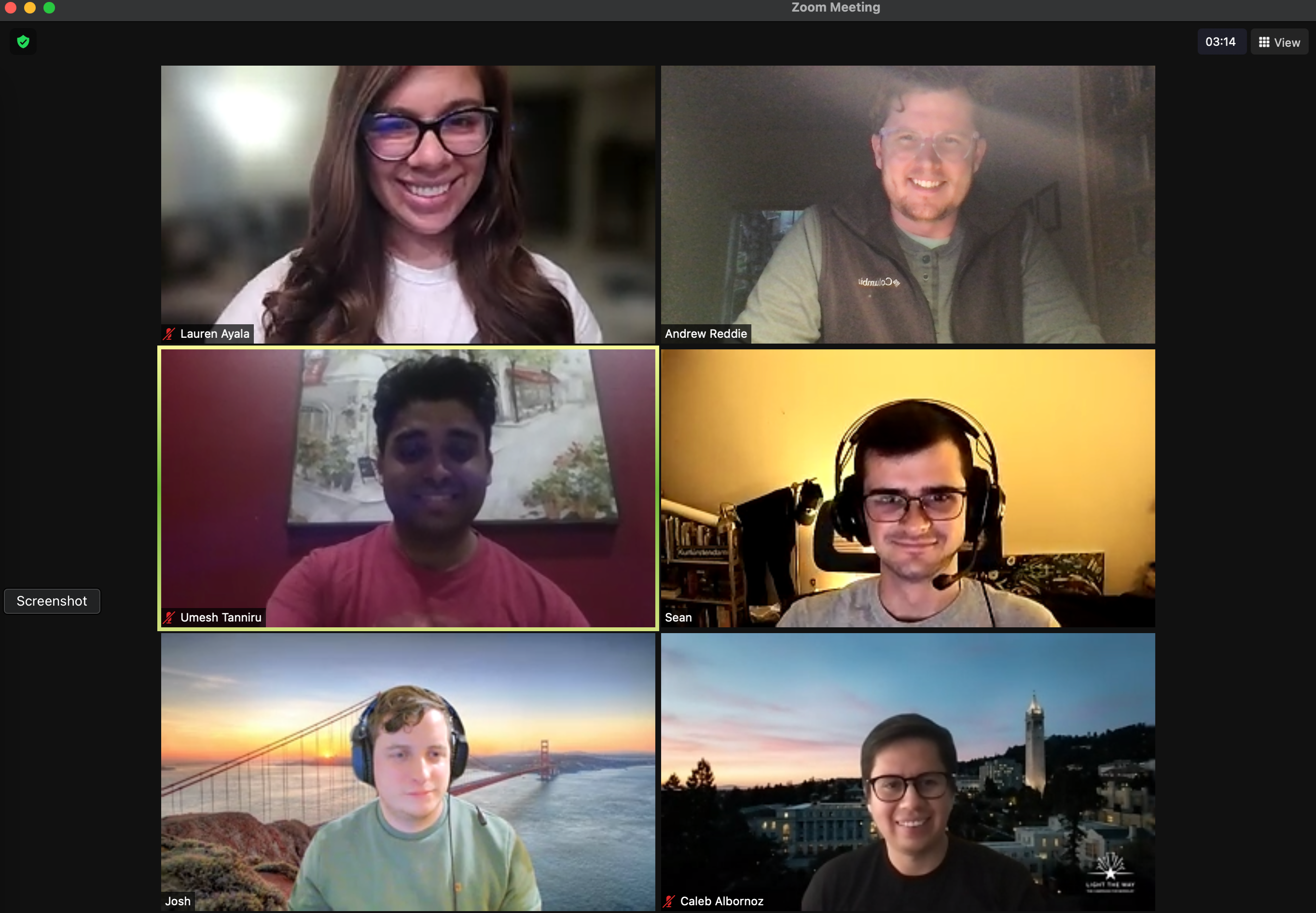

135 teams from colleges and universities around the United States, including two from the School of Information’s Master of Information and Cybersecurity program — “HotMICS” and “SeisMICS” — considered this scenario and frantically worked to thwart a simulated cyberattack in the Department of Energy’s 2021 CyberForce competition.

CyberForce

CyberForce began in 2016 with eight competing teams. The competition seeks to develop the next generation of cyber professionals to defend and protect our nation’s critical energy systems from cyber threats and attacks.

“As cyber threats grow and we continue to develop the clean energy grid of the future, recruiting and retaining a highly skilled workforce to protect and defend our nation’s energy systems is critical,” said Deputy Secretary of Energy David Turk. “I’m proud of the students who joined us this past weekend to expand their cyber skills and knowledge, while channeling their passion for cybersecurity.”

MICS Teams Rank

HotMICS ranked 6th overall, with SeisMICS placing 54th. The competition, held online on November 12 and 13, 2021, engaged teams in activities centered on energy-focused cybersecurity methods, practices, strategy, policy, and ethics, all while defending their network against red team attacks. Alumnus Thomas McCarty, MICS ’21, who served as a mentor and organizer for the teams said, “Many cybersecurity contests are a series of puzzles and challenges. The CyberForce Competition is unique in its realism. The team performs technical tasks, but their solutions must address stakeholder concerns from corporate executives, Industrial Control System (ICS) users, and network adversaries. The stakeholders are not fictitious — they’re also part of the competition.”

Three weeks before the event, teams were given access, instructions, and the criteria for judging. During that time teams enumerated the working environment and remediated as many vulnerabilities as they could find before the two-day event: anomaly puzzles were delivered to teams in an encrypted zip file and contained close to 50 exercises, which included log deciphering, malware analysis, and steganography exercises (message hiding).

The red-team exercise used an “assume breach” tactic, which assumes that your security has already been violated by an attacker at some point in time. Because the systems were intentionally broken and full of security holes — those systems were exploited by the hackers.

Solving Complex Security Problems

“We didn’t expect as many issues to be deeply embedded into the systems already,” HotMICS team lead Lauren Ayala said. “The ‘assume breach’ dynamic of the competition added a level of realism where an attacker accessed this system long in the past and set up some backdoors for their future access. Not only were we walking into an environment that was poorly designed and managed, a problem all security professionals know well, we also walked into one that was full of traps.”

Ismail Kably, the SeisMICS team lead, said his team lacked DevOps/Sysadmin experience, which affected their performance. “Our team was composed of three software engineers and one security engineer, and this challenged us outside of our main area of expertise.” He went on to say that the team considered the exercise a good learning experience.

McCarty said he was very impressed with the work done by the MICS teams. “In a very short time, our students fixed an inoperable network of equipment, secured that network and equipment, and during game day, supported users while the equipment was attacked over the network. In a field of talented competitors, their placement in the overall standings was amazing,” he said.

The I School students said that the event drove home the complexity of solving security problems—that even in a simulated environment, it’s difficult to build something safe, and, that it was a valuable learning experience to be able to operate in a simulated environment without the impact of a true site failure.

“The Department of Energy is facing a near-impossible problem in defending their infrastructure against sophisticated and unsophisticated actors alike,” Ayala said. “This competition encouraged all of our respect for those that do this work, every day. Ultimately, I think it’s safe to say we all had a really fun time, learned a lot about hardening the technology infrastructure, made some friends, and came out of this as better cyber security professionals.”